Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Mexican Patients with Chronic Pain

Mario Angel Rosas-Sanchez1, Argelia Lara-Solares2, Gloria Llamosa3, Maria Del Rocío Guillen Nunez4*, Ana Lilia Garduno5, Andrea del Bosque6, Paola Elorza7

1Professor of Pharmacology at Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Mexico. Faculty of Medicine. Toluca, State of México. México

2Department of Pain and Palliative Medicine. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City.

3President - Mexican Society of Neurology and Psychiatry (Sociedad Mexicana De Neuroglia Y Psiquiatria)

4Director of Alive Medical Clinic, Mexico City, Mexico

5Department of Anesthesiology and Acute Postoperative Pain Service at Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán.

6Research, Development & Medical, Upjohn – A Pfizer Division, Mexico City, Mexico

7Research, Development & Medical, Upjohn – A Pfizer Division, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- *Corresponding Author:

- Maria Del Rocio Guillen Nunez

Director of Alive Medical Clinic, Tlalpan, 14050 Ciudad de México, Mexico City,

Mexico

Email: roca8gnz@gmail.com

Received date: September 21, 2022, Manuscript No. IPMCR-22-14610; Editor assigned date: September 23, 2022, PreQC No. IPMCR-22-14610 (PQ); Reviewed date: September 30, 2022, QC No IPMCR-22-14610; Revised date: October 07, 2022, Manuscript No. IPMCR-22-14610 (R); Published date: October 14, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2471-299X.8.10.136

Citation: Sanchez MAR, Solres AL, Llamosa G, Nunez MDRG, Garduno AL, et al. (2022) Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Mexican Patients with Chronic Pain. Med Clin Rev Vol. 8 Iss No.10:136.

Abstract

The objective of this semi-systematic review identifies the challenges and barriers to patient journey optimization in various chronic pain such as low back pain, neuropathic pain, and osteoarthritis in Mexican patients and explores opportunities in the health system to establish a patientcentric chronic pain management model.

Information on a patient journey in chronic pain in Mexico (awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control) was obtained from Embase, MEDLINE and BIOSIS, and national and global public portals. Data gaps were bridged by regional insights from experts. Except for the treatment, an alarming situation was observed for all touchpoints for chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis. A worse scenario was found for neuropathic pain with all the touchpoints affected.

Evidence-informed healthcare decisions, continuing medical education for pain management, and an increase in patient awareness may bring improvement in Mexico.

Keywords

Chronic pain; Pain; Neuropathic pain.

Introduction

According to the Global Disease Burden (GBD) Survey in 2016, chronic low-back pain attributed to 56.7 million totals Years Lived in Disability (YLD) [1]. Moreover, the 2017 GBD survey observed that low back pain corresponded to a major proportion of YLDs with continuing increasing trend in percentage change from 1990 to 2017, thereby becoming the leading cause of disability for both genders [2]. The prevalence of chronic pain in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) ranged from 6% (for typical conditions like fibromyalgia) to 48% (for common conditions majorly including musculoskeletal pain) in the general adult population as per a systematic review in 2016 [3]. The annual prevalence of low back pain among the adult United States (US) population was 10% to 30% in 2001 and the lifetime prevalence of low back pain in US adults was as high as 65% to 80% [4] in 2010. The prevalence of low back pain in Latin America was found to be within this range (30%) in 2014 [5]. Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts or recurs for more than 3 months [6].

Chronic Low Back Pain With A Neuropathic Component (CLBPNeP) is difficult to diagnose because lack of a gold-standard approach [7,8] and also has a significant impact on patient’s adherence to the treatment. Comorbid risk factors like diabetes and mental health conditions may further aggravate the pain perception. Hence, the prevalence of chronic pain is likely to be estimated incorrectly due to overestimation from false diagnoses or underestimation due to lack of awareness.

The Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) model will be used to guide study selection and to align the eligibility criteria with the research questions. Here, we will include an article that investigates what has been developed and/or evaluated for patients with chronic pain and OA (population), including data on clinical outcomes through knowledge of epidemiology and deterministic factors in chronic low back pain, OA, and Neuropathic pain management (concept). The context will be limited to a specific geographic location. Full-text quantitative or qualitative studies published from 2010 to 2019 will be included.

Overall quality improvement of Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) care relies on common touch points of the patient journey awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control [9]. Hence, evaluation of a patient journey based on these touchpoints along with overall clinical benefit (disease control) and its prevalence would provide actionable insights for better clinical decisions. Currently, patient journey data for chronic pain management are scarce in Mexico, and very few studies covering regional epidemiology are available. The primary objective of this article was to establish evidence based on patient journey components and further identify barriers against patient journey optimization in chronic pain patients (low back pain, neuropathic pain, and Osteoarthritis (OA). Additionally, this review will explore opportunities in the current Mexican health system to establish a patient-centric chronic pain management model.

Materials and methods

Study design

We performed a semi-scoping review with a structured and unstructured search. The detailed methodology for undertaking this review has been published recently [10]. The databases considered for the structured search were Embase, MEDLINE, and BIOSIS through the OVID platform, and the sources for the unstructured search included websites of the World Health Organization (WHO), Mexican Ministry of Health, the Incidence and Prevalence Database (IPD), and Google. A comprehensive search strategy was developed to retrieve articles with data on a patient journey for chronic pain in Mexico. Chronic pain was defined as pain lasting >3 months [11], including osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain. Neuropathic pain was defined as pain due to a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system [12], including diabetic peripheral neuropathy and low back pain with a neuropathic component. There were additional targeted literature searches in consultation with local subject matter experts performed to get data on the subject matter and for guidance on health system-related issues. Retrieved records were screened by an independent reviewer and verified by another independent reviewer for a bias-free and error-free approach. Original articles published in the English language from 2010 to 2019, with the information relevant to the research question, were considered for analysis. Local experts validated the analyzed data and supplemented the data gaps by providing regional data in the form of scientific articles, anecdotal data, and textual notes by subject matter experts. In considering the broader context, we adopted Scoping Review Research Question Framework (SRRQF). As per the debate by Munn Z in 2018, Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) mnemonic is recommended [13]. Accordingly, the research question components could be given in Table 1 below.

| Population (P) | Concept (C) | Context (C) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with chronic pain | Improvement in clinical outcomes through knowledge of epidemiology and deterministic factors | Mexico |

| Challenges and opportunities in patient journey |

Table 1: PCC mnemonic for scoping review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

(i) peer-reviewed published systematic review and/or meta-analysis, randomized controlled study, observational study, and narrative reviews in English;

(ii) focused on the adult human population aged ≥ 18 years;

(iii) reporting quantitative data from the patient journey touchpoints for CLBP, OA, and Neuropathic, which includes awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control;

(iv) Full-text peer-reviewed articles (English language only);

(v) studies conducted on patient populations with chronic pain conditions, which is characterized as any pain continuing for longer than 3 months, focusing exclusively on LBP, OA, and Neuropathic.

Studies were excluded if they were published before 2010, languages other than English, case studies, letters to the editor, studies with specific patient subgroups, and duplicate records.

Data extraction

The extracted data included quantitative information on patient journey touchpoints (awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control). It also covered qualitative aspects like challenges in the patient journey, future opportunities, and also situational analysis of existing healthcare gaps. In addition, the content was extracted, including prevalence, associated factors, outcomes, and management of chronic pain.

Additionally, forward-looking strategies for optimizing patient outcomes were noted in the context of Mexico.

Results

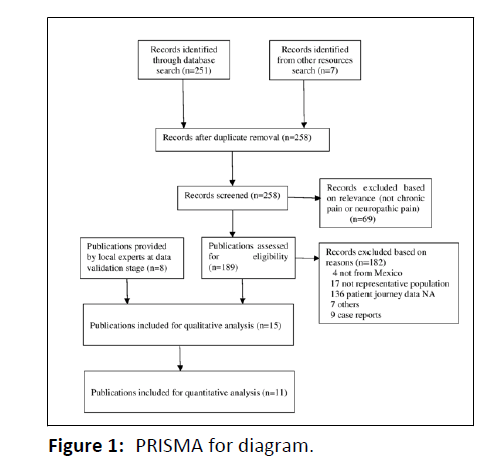

A total of 258 records were retrieved from structured and unstructured searches based on the search strategy. No duplicates were found. On the basis of the relevance to the subject and study objectives, 69 records were excluded. Of 189 screened records, 182 records were excluded based on a mismatch with the country of interest, inclusion criteria, target population characteristics, and patient journey data requirements. This included seven articles excluded for miscellaneous reasons and 9 case reports. To fill the data gaps, eight additional records on both chronic and neuropathic pain were provided by the experts for local insights. Thus, 15 and 11 records were considered for qualitative and quantitative synthesis of extracted data respectively. Preferred Reporting Items For Systematic Reviews And Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram showing the process of data mining is given below (Figure 1).

Treatment was found at 51.6% and 53% for CLBP and OA. Collectively, 49.2% of neuropathic patients (DPN) were treated. The details of records included in the final analysis are provided in Table 2.

| S. No. | Author(s) & Year | Title | Indication | Sample Size | Prevalence (%) | AW (%) | SC (%) | DG (%) | TR (%) | AD (%) | CT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Esquivel-Valerio JA et al. 2018 [14] | The Impact of Osteoarthritis on the Functioning and Health Status of a Low-Income Population: An Example of a Disability Paradox | OA | 439 | 83 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Del Rio Najera D et al. 2016 [15] | Rheumatic Diseases in Chihuahua, Mexico: A COPCORD Survey | OA | 1006 | 21.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | Jacqueline Rodriguez-Amado et al. 2011 [16] | Epidemiology of Rheumatic Diseases. A Community-Based Study in Urban and Rural Populations in the State of Nuevo Leon, Mexico | OA, CLBP | 4713 | 38.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | Joao BS Garcia, et al. 2014 [5] | Prevalence of Low Back Pain in Latin America: A Systematic Literature Review | CLBP | 3,361 | 8.10% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | Hernandez-Caceres A, et al. 2014 [17] | Kneeling disability associated with the treatment of osteoarthritis: Analysis of a COPCORD study in Mexico | OA | 696 | - | - | - | - | 71 | - | - |

| 6 | Espinosa R et al 2018 [18] | Reunión Multidisciplinaria de expertos para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la OA. Actualización basada en Evidencias | OA | - | 10.5 | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| 7 | Mejía-Espinosa y cols. et al. 2014 [19] | Prevalencia del dolor de espalda baja en un centro interdisciplinario para el estudio y tratamiento del dolor | CLBP & NP | 780 | 30.9 | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| 8 | González-Duarte A1 et al. 2016 [20] | The Efficacy of Pregabalin in the Treatment of Prediabetic Neuropathic Pain | DPN | 45 | - | - | - | - | 36 | - | - |

| 9 | Fernando Carlos et al. 2011 [21] | Economic evaluation of duloxetine as a first-line treatment for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Mexico | DPN | 4000 | - | - | - | - | + | + | - |

| 10 | Arellano-Longinos SA et al. 2018 [22] | Prevalencia de neu- ropatía diabética en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en una clínica regional del Estado de México | T2DM | 106 | 80 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública 2016 [23] | Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición de Medio Camino 2016 (ENSANUT 2016) | DPN | 29,795 | 41.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12 | Hernández-Ávila et al.2013 [24] | Diabetes mellitus en México. El estado de la epidemia | DPN | - | + | - | - | 9.17 | - | - | - |

| 13 | Espín-Paredes E y cols et al. 2010 [25] | Factores de riesgo asociados a neuropatía diabética dolorosa | DPN | 87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 14 | Ramírez-López et al.2017 [26] | Neuropatía diabética: frecuencia, factores de riesgo y calidad de vida en pacientes de una clínica de primer nivel de atención | DPN | 97 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | Shillo P et al. 2019 [27] | Painful and Painless Diabetic Neuropathies: What Is the Difference? | DPN | 3250 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | Anecdotal Data from Regional Experts | Key country-local opinion leaders average | OA, CLBP, CLBP-NeP and DPN | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Table 2: Details of records included in the final analysis.

As per ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 reports, the prevalence of diabetic complications including burning or loss of sensation in the soles of feet were 38.08% [24] and 41.2% [23], respectively. Another study on 87 diabetic patients in Mexico found that the proportion of patients with painful DPN (58.60%) was more than that with non-painful DPN (44.40%) [25]. A study in recent past in 2017 estimating the prevalence of DPN indicated that although the overall percentage of DPN ranged between 20%-30%, from this percentage, the subtype of neuropathic pain most frequently found was electric discharge pain type (20.6%), followed by burning pain (17.5%), rubbing pain (9.35%) and cold pain (9.3%) [26].

Population, Concept and Context (PCC)

The majority of patients with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain used over-the-counter Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) on the basis of self-prescription or even alternative therapies despite questionable efficacy and safety [15].

While OA and other rheumatic diseases were found prevalent in the rural population, the urban population had a comparatively higher prevalence of low back pain.

Discussion

We performed a semi-systematic review of available evidence on pain management scenarios in Mexico for patients with chronic pain conditions including OA, CLBP, CLBP-NeP, and DPN using a scoping review research framework (PCC model). This framework was suitable for this study as there was limited information available on various challenges in chronic pain care pathways. Moreover, the available information was heterogeneous and fragmented. Thus, an exploratory approach with comprehensive nature was deemed fit for our analysis.

Major concerns related to chronic pain care pathways in Mexico were observed in form of poor resource allocation, lack of well-defined patient transit algorithms including effective referrals, and sub-optimal knowledge dissemination due to resource constraints. The nutshell representation of the challenges can be seen in Table 2.

There is a significant d earth o f up-to-date clinical practice guidelines on pain management. Also, the status of validated pain screening/diagnosing tools in Spanish is not known. Clinical practice guidelines are available for public hospitals; however, their review has been pending for almost a decade. Thus, up-todate knowledge is not available to care practitioners on pain management. Also, there is the likelihood of ineffective clinical outcomes from alternative therapies with unclear regulations, fragmented availability, and limited knowledge of practitioners [28].

The integration of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) into policy decisions could be an effective strategy for achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC). The use of opioids in managing chronic pain remains controversial amongst clinicians [29,30]. Efficient resources leveraged through value-oriented policy analysis may also help save financial resources which could be allocated for the clinical development of first-line prophylactic drugs for chronic pain.

For low back chronic pain, the presence of ‘red flags’ for urgent medical conditions and ‘yellow flags’ for a psychosocial situation could prove beneficial. Both pain and mental health conditions could threaten the therapeutic outcomes and hence the information on the red and yellow flags for CLBP and CLBPNeP should be promoted [31,32]. Additionally, guidelines and algorithms for the management of different chronic pain syndromes from an educational techniques perspective focused on learning for adults should be propagated [33]. These could work better when implemented from basic medical education and should be strengthened for GPs, where current educational strategies guided by Andragogy could be more useful. Overall, improvement in the current medical education system in Mexico is a need of the hour and can be achieved by the focus on devising novel models of learning and development ingrained in the concepts of Andragogy. Newer strategies for adult learning must be implemented to train GPs to optimize the outcomes in the better management of the patient's pain [34].

Given the emergence of an evidence-based approach to care delivery, real-world evidence and patients reported outcomes have gained immense research interest [35]. Such sources could be developed for Mexican chronic pain patients and a researchintensive environment could be created. Also, there is scarce data available on painful DPN prevalence. Nevertheless, the tenitems table implied neuropathic pain, thereby emphasizing the need for attention towards rubbing pain regardless of its small prevalence compared to that of DPN.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that for both chronic pain and neuropathic pain, patient journey touch points showed an alarming situation. The existence of a known-do gap, a high degree of heterogeneity in the target population, and subjective concerns impede the translation of pain management from evidence to practice in Mexico. Given the treatment challenges due to resource constraints, subjective preferences of GPs, and issues related to patient perceptions in Mexico. Thorough observation and analysis of health-seeking behavior and associated clinical needs may help to better understand pain from the patient’s perspective. Also, unlike the current case of provider-driven decision-making, patients should be educated, encouraged, and empowered for shared clinical decisionmaking.

Last but not the least, outcome-oriented research like our study would be given paramount importance given the fact of booming use of patient-reported outcomes and health care quality. This would include components like periodic reviews of patient satisfaction, treatment feedback, patient engagement, and a high degree of research inclination towards the quality-oflife studies and economic evaluation of healthcare interventions, to name a few.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the experts who provided insights for bridging the data gaps. The support provided by the independent reviewer, Aditi Karmarkar from Upjohn-a Pfizer division, is deeply acknowledged. We thank Kaveri Sidhu from Upjohn -a Pfizer division for critically reviewing the draft. The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge Kapil Khambholja and the Indegene team’s support for medical writing and reviewing services for this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 390: 1211-59.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, et al. (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 392: 1789-858.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V, Shotwell M, Han X, et al. (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the global burden of chronic pain without clear etiology in low-and middle-income countries: Trends in heterogeneous data and a proposal for new assessment methods. Anesth Analg 123: 739-48.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Urits I, Burshtein A, Sharma M, Testa L, Gold PA, et al. (2019) Low back pain, a comprehensive review: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep 23: 1.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Garcia JB, Hernandez-Castro JJ, Nunez RG, Pazos MA, Aguirre JO, et al. (2014) Prevalence of low back pain in Latin America: A systematic literature review. Pain Physician 17: 379-391.

[Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, et al. (2019) Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 160: 19-27.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Mehra M, Hill K, Nicholl D, Schadrack J. (2012) The burden of chronic low back pain with and without a neuropathic component: A healthcare resource use and cost analysis. J Med Economics 15: 245-52.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Baron R, Binder A, Attal N, Casale R, Dickenson AH, et al. (2016) Neuropathic low back pain in clinical practice. European J of pain 20: 861-73.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Devi R, Kanitkar K, Narendhar R, Sehmi K, Subramaniam K (2020) A narrative review of the patient journey through the lens of non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries.- Adv Ther 1-23.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Bharatan T, Devi R, Huang PH, Javed A, Jeffers B, et al. (2021) A Methodology for Mapping the Patient Journey for Noncommunicable Diseases in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. J Healthc Leadersh 13: 35.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016.

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, et al. (2017) Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3: 1-9.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, et al. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Research Method 18: 1-7.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- EsquivelValerio JA, Orzua de la Fuente WM, Vázquez-Fuentes BR, Garza Elizondo MA, Negrete-López R, et al. (2018) The impact of osteoarthritis on the functioning and health status of a low-income population: An example of a disability paradox. JCR: J Clinic Rheumatolo 24: 57-64.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Nájera DD, González-Chávez SA, Quiñonez-Flores CM, Peláez-Ballestas I, Hernández-Nájera N, et al. (2016) Rheumatic diseases in Chihuahua, México: a COPCORD survey. JCR: J Clin Rheumatolo 22: 188-93.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Rodriguez-Amado J, Peláez-Ballestas I, Sanin LH, Esquivel-Valerio JA, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. (2011) Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases. A community-based study in urban and rural populations in the state of Nuevo Leon, Mexico. The J Rheumatolo Supplement 86: 9-14.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Hernández Cáceres A, Rodríguez Amado J, Peláez-Ballestas I, Vega Morales D, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. (2014) Kneeling disability associated with the treatment of osteoarthritis: analysis of a copcord study in Mexico. Arthritis Rheumatolo 66.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Espinosa-Morales R, Alcántar-Ramírez J, Arce-Salinas CA, Chávez-Espina LM, Esquivel-Valerio JA, et al. (2018) Multidisciplinary meeting of experts for diagnosis and treatment of osteoarthritis. Up-to-date based on evidence. Roland Esp Internal Medicine of Mexico 34: 443-476.

- Covarrubias-Gómez A, Guevara-López U, De Lille-Fuentes R, Ayón-Villanueva H, Gaspar-Carrillo SP, et al. (2014) First national summit of delegates of the Mexican Association for the Study and Treatment of Pain. Rev Mex Anest 37: 142-147.

- González-Duarte A, Lem M, Díaz-Díaz E, Castillo C, Cárdenas-Soto K (2016) The efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of prediabetic neuropathic pain. The Clin J Pain 32: 927-932.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Carlos F, Ramírez-Gámez J, Dueñas H, Galindo-Suárez RM, Ramos E (2012) Economic evaluation of duloxetine as a first-line treatment for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Mexico. J Med Econ 15: 233-244.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Arellano Longinos SA, Godínez Tamay ED, Hernández Miranda MB (2018) Prevalence of diabetic neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a regional clinic in the State of Mexico. Fam Med 25: 1.

- Shamah-Levi T, Cuevas-Nasu L, Dommarco-Rivera J, Hernandez-Avila M (2016) Midway National Health and Nutrition Survey (2016). Inst Nac Public Health 151.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Hernández-Ávila M, Gutiérrez JP, Reynoso-Noverón N (2013) Diabetes mellitus in Mexico: The state of the epidemic. Public health of Mexico 55: 129-136.

[Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Espín-Paredes E, Guevara-López U, Arias-Rosa JC, Pérez-Carranco ML (2010) Risk factors associated with painful diabetic neuropathy. Rev Mex Anestesiol 33: 69-73.

- Ramírez-López P, Acevedo Giles O, González Pedraza AA (2017) Diabetic neuropathy: Frequency, risk factors and quality of life in patients of a primary care clinic. Archivos n medicina familiar 19: 105-111.

- Shillo P, Sloan G, Greig M, Hunt L, Selvarajah D, et al. (2019) Painful and painless diabetic neuropathies: what is the difference?. Curr Diabetes Reports 19:32.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Amescua-Garcia C, Colimon F, Guerrero C, Jreige Iskandar A, Berenguel Cook M, et al. (2018) Most relevant neuropathic pain treatment and chronic low back pain management guidelines: A change pain Latin America advisory panel consensus. Pain Med 19: 460-470.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Rosenblum A, Marsch LA, Joseph H, Portenoy RK (2008) Opioids and the treatment of chronic pain: controversies, current status, and future directions. Exp and Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 405.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Goodman-Meza D, Medina-Mora ME, Magis-Rodríguez C, Landovitz RJ, Shoptaw S, et al. (2019) Where is the opioid use epidemic in Mexico? A cautionary tale for policymakers south of the US–Mexico border. American J Public health 109:73-82.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Will JS, Bury DC, Miller JA (2018) Mechanical low back pain. Am Fam Physician 98: 421-428.

[Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Amescua-Garcia C, Colimon F, Guerrero C, Jreige Iskandar A, Berenguel Cook M, et al. (2018) Most relevant neuropathic pain treatment and chronic low back pain management guidelines: A change pain Latin America advisory panel consensus. Pain Med 19: 460-470.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Lockman K, Thomas D, Hill LH (2019) Adult learning theories in pharmacy education. J Res Pharm Pract 389-397.

- Jacobs ZG, Elnicki DM, Perera S, Weiner DK (2018) An E-learning Module on Chronic Low Back Pain in Older Adults: Effect on Medical Resident Attitudes, Confidence, Knowledge, and Clinical Skills. Pain Med 19: 1112-1120.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

- Bellows BK, Kuo KL, Biltaji E, Singhal M, Jiao T, et al. (2014) Real-world evidence in pain research: A review of data sources. J Pain and Palliative Care pharmacoth 28: 294-304.

[Crossref], [Google scholar], [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences