Isolated Double-chambered Right Ventricle - A Rare Congenital Heart Disease: Case Report and Literature Review

Sarita Choudhary

DOI10.21767/2471-299X.1000019

D.M. Cardiology, S.M.S Medical College Jaipur, Jaipur, Rajasthan India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Sarita Choudhary

D.M. Cardiology, S.M.S Medical College

Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Tel: 919460467362; 09413384988

E-mail: drsaritachoudhary@yahoo.com

Received date: December 02, 2015; Accepted date: April 25, 2016; Published date: April 29, 2016

Citation: Choudhary S,Isolated Double-chambered Right Ventricle - A Rare Congenital Heart Disease: Case Report and Literature Review.Med Clin Rev. 2015, 2:10. doi: 10.21767/2471-299X.1000019

Copyright: © 2016 Choudhary S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

A double-chambered right ventricle (DCRV) is a rare congenital heart disease and an uncommon cause of congestive cardiac failure. An anomalous muscle band (AMB) divides the right ventricle into two cavities, the proximal high-pressure chamber and distal low-pressure chamber. Its origin is debated. Most cases are diagnosed and treated during childhood. Furthermore, there is tendency for progression, if not treated. Echocardiography is considered useful for diagnosis. 80-90% patients have associated congenital anomalies, such as ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, and subaortic stenosis. Isolated DCRV is exceptionally rare. Hence, we report a case of an isolated DCRV adult patient who was asymptomatic.

Keywords

Double chamber ventricle; Muscle bundle; Anomalous muscle band; Right heart failure; Right ventricle

Case Report

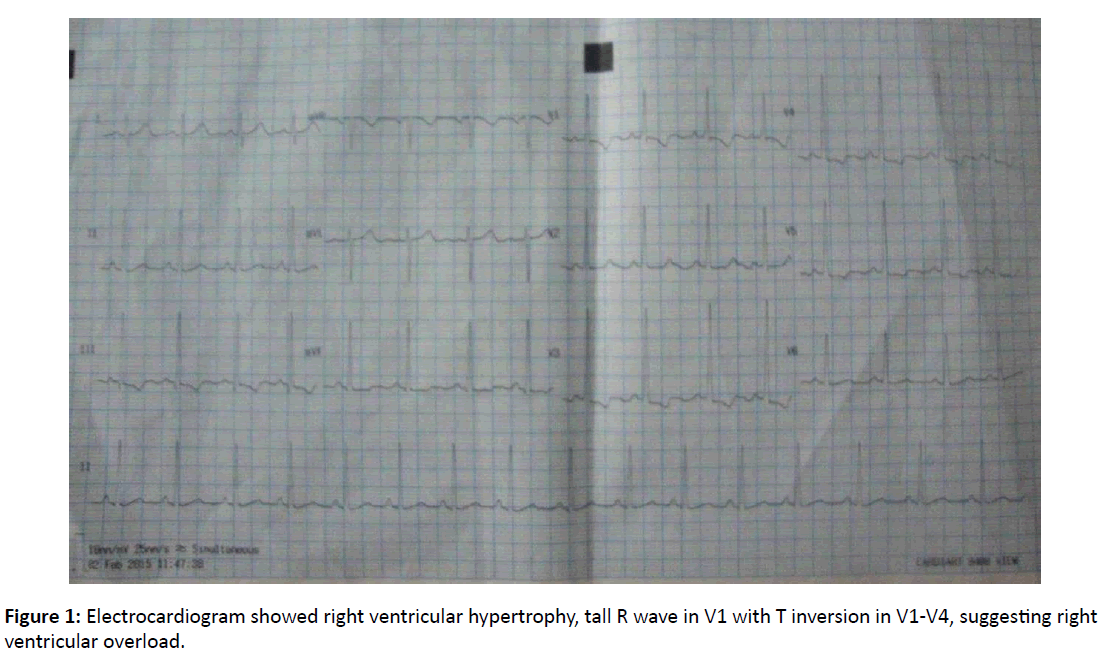

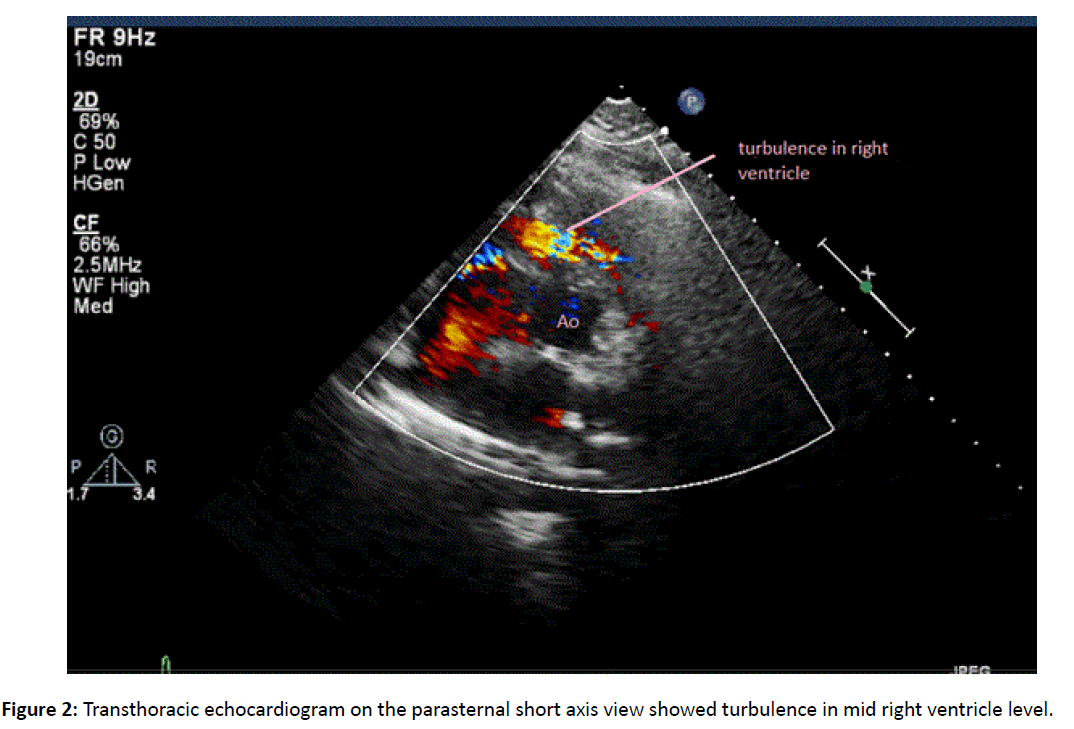

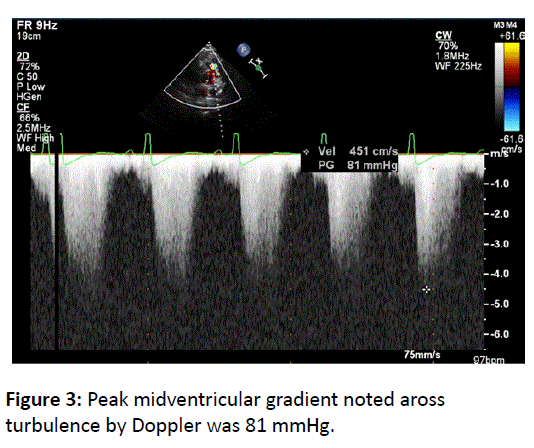

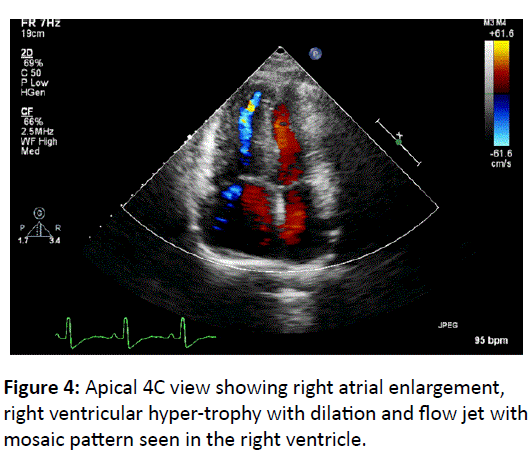

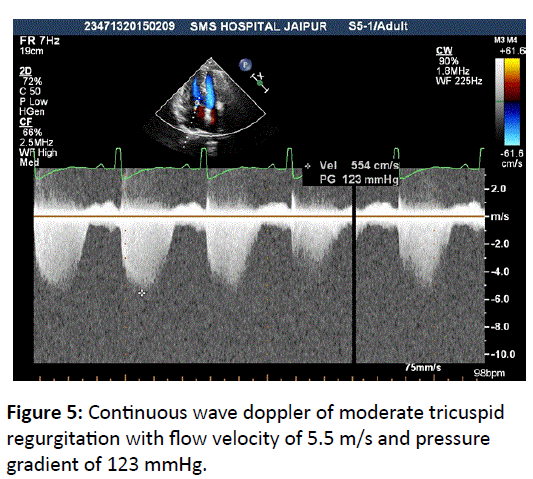

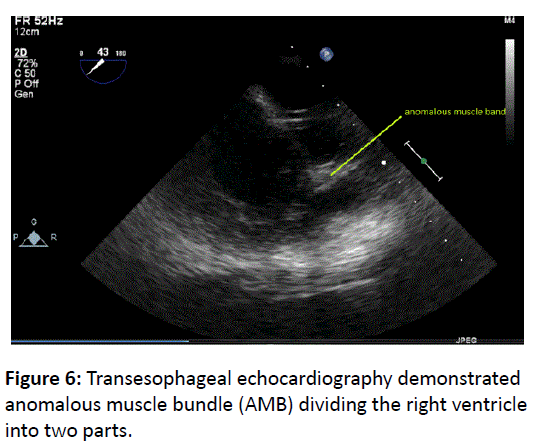

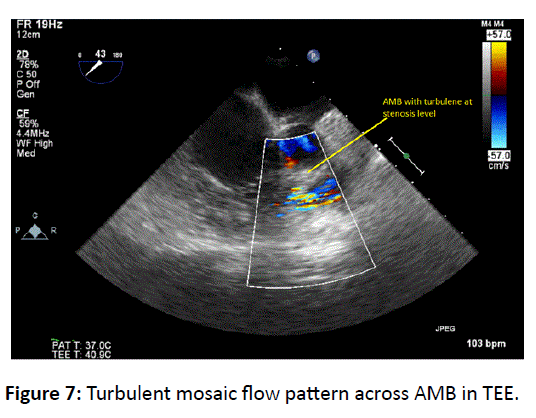

A 28-year-old female was referred to hospital for evaluation of cardiac murmur found during medical checkup for epistaxis. The patient had no cardiac symptoms, such as chest pain or dyspnea. She was 5 months pregnant. First chid was 3 year girl by uncomplicated vaginal delivery. On examination a loud harsh systolic ejection murmur, grade IV/VI was heard at the third and fourth left intercostals space. S1 and S2 were normal. Electrocardiogram showed right ventricular hypertrophy, tall R wave in V1 with T inversion in V1-V4, suggesting right ventricular overload (Figure 1). Chest X-ray was not done as patient was pregnant. Transthoracic echocardiogram on the parasternal short axis view showed turbulence in mid right ventricle level but no muscle bundle could be seen clearly (Figure 2) peak midventricular gradient by Doppler was 81 mmHg (Figure 3). In apical 4C view right atrial enlargement, right ventricular hypertrophy with dilation and flow jet with mosaic pattern was seen in the right ventricle (Figure 4). Continuous wave Doppler revealed moderate tricuspid regurgitation with flow velocity of 5.5 m/s and pressure gradient of 123 mmHg (Figure 5). Biventricular systolic function were normal. Transesophageal echocardiography demonstrated anomalous muscle bundle dividing the right ventricle into two parts (Figure 6) with turbulent mosaic flow pattern across it (Figure 7). There was no shunt flow between the right and left parts of the heart. There was no pressure gradient between the right ventricle outlet tract and the main pulmonary artery. Based on these findings, the patient was advised for surgical correction, but the patient refused operative correction and was thus discharged.

Introduction

Double-chambered right ventricle (DCRV) is a developmental cardiac anomaly in which aberrant muscular band obstructs the body of right ventricle dividing it into highpressure proximal chamber and low-pressure distal chamber. It was first described by Tsifutis and Lucas et al. described two unrecognized cases of DCRV in which inadvertent closure of transventricular channel, which was mistaken for ventricular septal defect (VSD) had fatal outcome [1]. Probably this condition is present at birth but without significant gradient. In patients with VSD increased blood flow and pressure within right ventricular outflow tract may act as initial stimulus for

hypertrophy of crista supraventricularis. The obstruction in right ventricle deteriorates further [2]. Anomalous muscle bundle (AMB) occurs below the infundibulum and extends from its anterior wall to crista upraventricularis or interventricular septum. Attachments to chordae of tricuspid valve or anterior papillary muscle are noted occasionally. Not infrequently, multiple small muscle bundles occur.

The origin of the AMB is unknown. Possible theories are failure of resorption of fetal trabeculations or due to hypertrophy of oblique component of the bulbar musculature. Right ventricular subdivision and obstruction may represent arrested incorporation of the primitive bulbus cordis into right ventricular body [3]. The irregular expansion of bulboventricular junction results in incomplete fusion of the bulbar and endocardial cushion which normally closes superior portion of the ventricular septum, thus explaining frequent association of VSD with DCRV. Subtypes of DCRV reported are anomalous septoparietal band, hypertrophy of apical trabeculations, anomalous apical shelf and sequestration of the outlet portion of the ventricle. However, no uniformity is observed in the position of these AMB [4].

DCRV accounts for 0.5-2% of congenital heart disease and occurs in as many as 10% of patients with VSD [5]. Male-tofemale ratio is 2:1. No inheritance pattern or risk factors are described. Sporadic cases reported in patients with Down and Noonan Syndromes. Associated congenital cardiac abnormalities are found in 80-90% cases. Isolated DCRV is exceptionally rare [6]. VSD is the most common defect, next being pulmonary stenosis. Other associations are doubleoutlet right ventricle, tetralogy of Fallot, anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, transposition of the great arteries, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, and Ebstein anomaly [7]. VSD is usually large, perimembranous and opens into high pressure proximal chamber but it may open into distal chamber also. As the obstruction worsens associated VSD may progressively become smaller. Few report that asymptomatic adults with AMB and intact ventricular septum may have had VSD that underwent spontaneous closure [8].

Its clinical significance would depend upon degree of obstruction and associated lesions [3]. Presentation is commonly in childhood but can be as early as newborn period. The commonest symptoms are dyspnea and decreased exercise tolerance. However cyanosis, syncope, chest pain, endocarditis and heart failure are reported. Clinically, patients with isolated DCRV resemble patients with pulmonary stenosis. Auscultation reveals systolic ejection murmur at upper-mid left precordium. Electrocardiogram shows right ventricular hypertrophy but may show evidence of diminished terminal right ventricular forces.

The increased hemodynamic load of pregnancy may precipitate right heart failure, atrial arrhythmias, or tricuspid regurgitation in patients with significant right ventricle outflow tract obstruction, irrespective of the presence or absence of symptoms prior to pregnancy. Women should be advised to meet with their cardiologist prior to becoming pregnant so that their baseline status can be determined. Ideally, symptoms should be addressed prior to pregnancy with a surgical intervention, if necessary.

For diagnosis transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) may be insufficient, so transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is strongly advised for both children and adults, particularly in the presence of right ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram. It can be difficult to obtain an image owing to the proximity of the right ventricular outflow tract to the transducer. Colour flow Doppler identifies the site of obstruction by the appearance of a mosaic pattern where the high-velocity flow originates [5,8]. Cardiac catheterisation may be performed to confirm the diagnosis. The catheter must be placed in inflow portion of right ventricular and pressure gradient is demonstrated as the catheter is advanced into distal, low-pressure chamber. Pressure in the distal chamber is equal to pulmonary artery unless there is associated pulmonary valve stenosis. Right ventricular angiography

showing filling defects within the right ventricle between the outflow and inflow areas, confirms the diagnosis. Left ventriculography is performed for associated VSD or subaortic stenosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance can visualize RV anatomy, obstructing muscular bundles together with a determination of the pressure gradient [9].

Treatment is surgical resection of AMB and repair of other anomalies at the same time. Surgery is recommended for patient with a peak midventricular gradient by doppler greater than 60 mmHg or a mean more than 40 mmHg, regardless of symptoms. In isolated asymptomatic DCRV, observation is appropriate till intracavitary gradient is less than 40 mmHg and obstruction is not progressive [10]. Resection of the anomalous muscle can be approached through right atriotomy, right ventriculotomy, or combined transatrial–transpulmonary incision. The long term results of surgical treatment are excellent. Need for reoperation for recurrent obstruction is

exceedingly uncommon.

Conclusion

DCRV has been reported as a rare disease in adults. Consequently, number of cases are missed and not diagnosed. Careful evaluation of DCRV by echocardiography including TEE is necessary, especially in patients with VSD. These patients should be treated surgically, because the obstruction is progressive and ends in heart failure.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- LucasRV, VarcoRL, LilleheiCW, ADAMS P, Anderson RC, et al. (1962) Anomalous muscle bundle of the right ventricle. Hemodynamic consequences and surgical considerations. Circulation 25:443.

- JWForster, Humphries JO(1971) Right Ventricular Anomalous Muscle Bundle: Clinical and Laboratory Presentation and Natural History. Circulation43: 115-127.

- Rowland TW, Rosenthal A, Castaneda AR (1975) Double chambered Right ventricle experience with 17 cases. Am Heart Journal 89: 455-462.

- Restivo A, Cameron AH, Anderson RH, Allwork SP (1984) Divided right ventricle: a review of its anatomical varieties. Paediatr Cardiol 5: 197-204.

- Hoffman P, Wojcik AW, Rozanski J, Siudalska H, Jakubowska E, et al. (2004) The role of echocardiography in diagnosing double chambered right ventricle in adults. Heart 90: 789-793.

- Park JI, Kim YH, Lee K, Park HK, Park CB (2007) Isolated double chambered right ventricle presenting in adulthood. Int J Cardiol 121: e25-e27.

- Lascano ME, Schaad MS, Moodie DS, Murphy D (2001) Difficulty in diagnosing double-chambered right ventricle in adults. Am J Cardiol88: 816-819.

- Matina D, van Doesburg NH, Fouron JC, Guérin R, Davignon A (1983) Subxiphoid two-dimensional echocardiographic diagnosis of double-chambered right ventricle. Circulation67: 885-888.

- Kilner PJ, Sievers B, Meyer GP, Ho SY (2002) Double-chambered right ventricle or sub-infundibular stenosis assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 4: 373-379.

- McElhinney DB, Chatterjee KM, Reddy VM (2000) Doublechambered right ventricle presenting in adulthood. Ann Thorac Surg70:124-127.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences