Update on Atopic Dermatitis: Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, and Treatment Selection

Ibrahim Mitwally and Manal Fawzy

1Department of Pediatrics, Saudi Arabian Airlines Medical services, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Pediatrics, Egyptian Board of Pediatrics, Egypt

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ibrahim Mitwally

Department of Pediatrics

Saudi Arabian Airlines Medical services, Saudi Arabia

E-mail:ibmitwally@yahoo.com

Received Date: April 21, 2020; Accepted Date: May 04, 2020; Published Date: May 11, 2020

Citation: Mitwally I, Fawzy M (2020) Update on Atopic Dermatitis: Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, and Treatment Selection. Med Clin Rev. Vol. 6 No. 2: 91.

DOI: 10.36648/2471-299X.6.2.91

Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as atopic eczema, is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin condition. Atopic dermatitis may occur in people of any age but often starts in infants aged 2-6 months. Ninety percent of patients with atopic dermatitis experience the onset of disease prior to age 5 years. Seventy-five percent of individuals experience marked improvement in the severity of their atopic dermatitis by age 14 years; The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in children with one affected parent is 60% and rises to nearly 80% for children of two affected parents. Additionally, nearly 40% of patients with newly diagnosed cases report a positive family history for atopic dermatitis in at least one first degree relative Atopic dermatitis persists into adulthood in 20-40% of children with the condition.

Introduction: Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of AD is not completely understood, however, the disorder appears to result from the complex interaction between defects in skin barrier function, immune dysregulation, and environmental and infectious agents. Skin barrier abnormalities ap- pear to be associated with mutations within or impaired expression of the filaggrin gene, which encodes a structural protein essential for skin barrier formation. The skin of individuals with AD has also been shown to be deficient in ceramides (lipid molecules) as well as antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidins. The infectious agent most often involved in AD is Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), which colonizes in approximately 90% of AD patients., These early effects lead to increased histamine release from IgE- activated mast cells and elevated activity of the T-helper cell mediated immune system. The increased release of vascular mediators (eg, bradykinin, histamine, slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis [SRS-A]) induces vasodilation, edema, and urticarial which in turn stimulate pruritus and inflammatory cutaneous changes.

Contact irritants, climate, sweating, aeroallergens, microbial organisms, and stress/psyche commonly trigger exacerbations. Food allergens like egg, soy, milk, wheat, fish, shellfish, and peanut, which together account for 90% of food-induced cases of atopic dermatitis in double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges. Fortunately, many clinically significant food allergies self-resolve within the first 5 years of life, eliminating the need for long-term restrictive diets [1-3].

Stress may trigger atopic dermatitis at the sites of activated cutaneous nerve endings, possibly by the actions of substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), or via the adenyl cyclase cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) system.

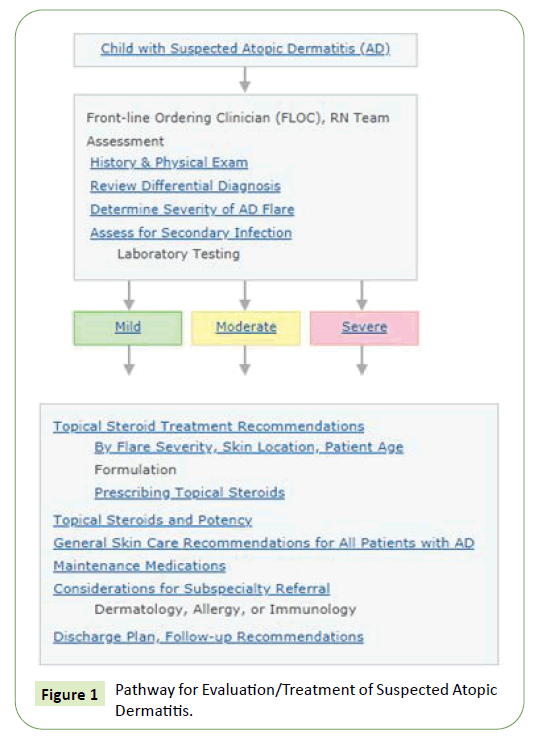

Pathway for Evaluation/Treatment of Suspected Atopic Dermatitis

The pathway for evaluation/treatment of Suspected Atopic Dermatitis is shown in the below figure (Figure 1).

History and examination

History and examination of Suspected Atopic Dermatitis is mentioned in the below table (Table 1).

Table 1 History and examination of Suspected Atopic Dermatitis.

| History | Duration of current symptoms |

| Acute, sub-acute, chronic | |

| Prior history of atopic dermatitis | |

| Last flare, regions of body usually affected | |

| Current medications for AD | |

| Routine skin care | |

| Bathing, shampoo, lotions, detergents | |

| Exposures, environment | |

| Pet dander, new environment, season change, etc. | |

| Sleep disturbance, behavioral changes | |

| History of | |

| Skin infections | |

| Allergies (food, seasonal, other environmental) | |

| Asthma | |

| Physical Exam | 1. Diagnostic criteria for AD |

| Major criteria Patient must have | |

| An itchy skin condition (or parental/caregiver report of scratching or rubbing in a child) | |

| Minor criteria | |

| Plus three or more of the following minor criteria | |

| History of itchiness in skin creases (e.g., folds of elbows, behind the knees, front of ankles, around the neck) | |

| Personal history of asthma or allergic rhinitis | |

| Personal history of general dry skin in the last year | |

| Visible flexural dermatitis (i.e., in the bends or folds of the skin at the elbow, knees, wrists, etc.) | |

| Onset under age 2 years | |

| History of atopic disease in a first-degree relative | |

| Eczema of cheeks, forehead and outer limbs | |

| 2. Total skin examination | |

| General Findings | |

| Keratosis pilaris on the upper arms, thighs and cheeks | |

| Hyper linear palms | |

| Darkening around eyes or scaling | |

| Lesions | |

| Note color, size, shape, texture, location | |

| Distribution of lesions | |

| Infants, toddlers: cheeks, extensor surfaces | |

| Older children: flexural creases | |

| Severity | |

| Mild: pink lesions with thin scale | |

| Moderate: thicker, more scale, skin may be darker in these areas, often widespread | |

| Severe: lichenified lesions, often on neck, wrists, ankles Patient may look red head to toe | |

| Sign of infection | |

| Crusting, scaling, weeping, erythema, increased pain | |

| Systemic symptoms |

Differential diagnosis for AD

Differential Diagnosis for Atopic Dermatitis is mentioned in the below table (Table 2).

Table 2 Differential diagnosis for AD.

| Irritant Dermatitis | Due to drooling, lip licking, diapers, clothing |

| Contact Dermatitis | Fragrances, metals, plants, chemicals, other |

| Seborrheic Dermatitis | Characterized by greasy scale on: |

| o scalp, eyebrows, central face, neck, chest, axilla, inguinal creases | |

| Occurs in infants, pre-adolescents, adolescents | |

| Infants can have an overlap between AD and seborrhea, this combined dermatitis may appear moderate to severe | |

| Psoriasis | In infants, usually affects the diaper area in contrast to AD |

| In older children, usually has a thicker scale and affects scalp and extensor surfaces of the skin | |

| Staphylococcal Infection | Peeling skin related to infection |

| Impetigo, Staph Scalded Skin | |

| Molluscum Contagiosum | Small skin colored papules with central umbilication caused by a pox virus |

| Can develop an underlying dermatitis | |

| Scabies | Infestation causes acute new itchy, widespread dermatitis |

| May include folded areas of skin, especially the genital area and interdigital spaces of the hands and feet | |

| Dermatophyte Infections | Can affect the scalp, skin or nails |

| Scalp lesions are associated with hair loss, itch, scale or boggi- ness | |

| Lesions on the body appear as scaly, annular patches |

Workout (Laboratory Studies)

No definitive laboratory tests

No definitive laboratory tests are used to diagnose Atopic Dermatitis (AD). Elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels and peripheral blood eosinophilia. Prick skin testing to common allergens can help identify specific triggers of atopic dermatitis For accuracy, antihistamines must be discontinued for 1 week and topical steroids for 2 weeks prior to testing [4,5].

Histologic findings

Acute eczematous lesions show histologic markings of hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis with a decreased or absent granular cell layer.

General Skin Care Recommendations for All Patients with AD

General skin care recommendations for all patients with Atopic Dermatitis is mentioned in the below table (Table 3).

Table 3 General Skin Care Recommendations for All Patients with AD.

| Bathing | Soak daily in lukewarm water, 5-10 minutes, if child enjoys bathing |

| If not, or if irritated skin, do every 2-3 days | |

| Use gentle, fragrance-free soap | |

| Avoid bubble bath | |

| Avoid wipe-down with washcloths, sponges, loofahs, baby wipes | |

| Pat skin dry after bath, leaving skin damp | |

| Emollients | Moisturize at least twice daily with cream or ointment (not lotion), more often as needed |

| Use petroleum jelly, or other fragrance-free moisturizer | |

| Apply within 3 minutes of bathing | |

| Apply topical steroid medication 30-60 minutes before emollient | |

| Application sooner dilutes medication effect | |

| Considerations to decrease irritation | Keep fingernails short |

| Use cotton clothing | |

| Wool, nylon, etc., may irritate the skin | |

| Avoid fragrances, perfumes around patients | |

| Use mild detergent | |

| all® Free and Clear, Tide® Free | |

| Avoid dryer sheets, fabric softeners | |

| Give diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine before bed to help sleep, ease itching as needed | |

| Wet wraps | Increase penetration of emollients and topical medicines |

| Decrease water loss | |

| Provide physical barrier against scratching | |

| Procedure: | |

| Apply emollient | |

| Wrap skin with layer of wet bandage or clothing | |

| Apply dry bandage or clothing over wet layer | |

| Bleach baths (for patients who are prone to superin- fection) | Add 1/4 cup unscented, regular, not concentrated Clorox bleach into 1/2 of regular sized bathtub |

| Bathe 5-10 minutes | |

| 1-3 times weekly | |

| Bleach Bath + |

Topical Steroids Treatment Recommendations by Flare Severity, Skin Location, Patient Age

Topical Steroids Treatment Recommendations by Flare Severity, Skin Location, Patient Age is mentioned in the below table (Table 4).

Table 4 Topical Steroids Treatment Recommendations by Flare Severity, Skin Location, Patient Age.

| Severity | Location | Age < 3 yrs Ointment covered by most insurance payers |

Age ≥ 3 yrs Ointment covered by most insurance payers |

Potency Class |

| Mild | Face/Genital s | 2.5% Hydrocortisone | 2.5% Hydrocortisone | Lowest Class VII |

| Mild | Body | 2.5% Hydrocortisone | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | Lower- Medium Class VI |

| Moderate | Face/Genital s | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | Lower- Medium Class VI |

| Moderate | Body | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | 0.1% Triamcino- lone acetonide | Medium Class V |

| Severe | Face/Genital s | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | 0.025% Triamcino- lone acetonide | Lower- Medium Class VI |

| Severe | Body | 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide | 0.05% Fluoci- nonide | High Class II |

Maintenance Medications for Outpatient Providers

Two weeks after the patient’s initial flare, consider switching to non-steroidal mainte- nance medication for patients who flare frequently such as one of the below (Table 5) [6].

Table 5 Maintenance Medications for Outpatient Providers.

| Medication | Age Range | Considerations |

| Crisaborole 2% (Eucrisa®) Cream | ≥ 2 years | · Can be used as treatment or maintenance |

| · Side effect: burning sensation | ||

| · Often not covered by insurance or is a step therapy requiring prior authorization | ||

| Pimecrolimus (Elidel®) Cream | ≥ 2 years | · Can be used for 4-6 weeks after acute flare medication |

| · Side effect: stinging/burning | ||

| Tacrolimus (Pro-topic®) Ointment | 2-16 years: 0.03% ointment ≥ 16 years: 0.1% ointment |

· Can be used for 4-6 weeks after acute flare medication |

| · Side effect: stinging/burning | ||

| · Often not covered by insurance or is a step therapy requiring prior authorization | ||

| · Keep in refrigerator to reduce burning effect | ||

| Anti-IL-4Ra thera- py (dupilumab) Dupilumab | Children >12 years | Sc injection administered every 2 weeks. |

Considerations for Subspecialty Referral

Considerations for subspecialty referral is mentioned in the below table (Table 6) [7,8].

Table 6 Considerations for Subspecialty Referral.

| Dermatology Re- feral | Uncertain diagnosis |

| Possibility of: Contact dermatitis Psoriasis Fungal Infection |

|

| History of recurrent skin infections | |

| Extensive/severe disease | |

| Management to date has not controlled symptoms | |

| Need for Class 1 topical steroid | |

| Allergy Referral | Mod/severe atopic dermatitis and known/suspected food allergies |

| Environmental triggers suspected | |

| Concomitant moderate or severe asthma | |

| Infants with severe atopic dermatitis | |

| Immunology Re- feral | Immunodeficiency or suspected immunodeficiency |

| History of recurrent fractures or infections in older patients | |

| Infants with severe atopic dermatitis and growth concerns, infections |

Outpatients

Most patients with AD do not need urgent consultation or outpatient referrals to Dermatology or Allergy/Immunology. Consider an expedited referral request to dermatology/allergy for:

• Severe or refractory disease

• Unclear diagnosis

• Suspected food allergy

• Suspected immunodeficiency Inpatients

• Consult for severe or refractory disease requiring escalation of treatment

• Initiation of systemic agents to control disease

• Severe or recurrent skin infections

• Concern for underlying immunodeficiency

Conclusion

AD is a complex disorder that requires both a genetic predisposition and exposure to poorly defined environmental factors. Disease results from a defective skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Effective treatment requires therapies targeted to both restoring barrier function and controlling inflammation. Treating both defects is crucial to optimal outcomes for patients with moderate to severe disease. Education of patients regarding the underlying defects and provision of a comprehensive skin care plan is essential.

References

- Egawa G, Kabashima K (2016) Multifactorial skin barrier deficiency and atopic dermatitis: essential topics to prevent the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol 38: 350-358

- Nomura T, Kabashima K (2016) Advances in atopic dermatitis in 2015. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138: 1548-1555.

- Tsakok T, Marrs T, Mohsin M, Baron S, du Toit G, et al. (2016) Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 137: 1071-1078.

- Lee JH, Son SW, Cho SH (2016) A comprehensive review of the treatment of atopic eczema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 8(3), 181-190.

- Kelleher M, Dunn Galvin A, Hourihane JO, Murray D, Campbell LE, et al. (2015) Skin barrier dysfunction measured by trans epidermal water loss at 2 days and 2 months predates and predicts atopic dermatitis at 1 year. J Allergy Clin Immunol 135:930-935.

- Kelleher MM, Dunn-Galvin A, Gray C, Murray DM, Kiely M, et al. (2016) Skin barrier impairment at birth predicts food allergy at 2 years of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137: 1111-1116.

- Pyun BY (2015) Natural history and risk factors of atopic dermatitis in children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 7: 101-105.

- Brough HA, Liu AH, Sicherer S, Makinson K, Douiri A, et al. (2015) Atopic dermatitis increases the effect of exposure to peanut antigen in dust on peanut sensitization and likely peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 135: 164-170.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences